One Party One Woman

When was concubinage abolished in China?

In 1922, the last emperor Puyi caused a stir. According to his teacher Reginald Johnston

“he surprised and shocked the court – especially the imperial dowagers – by vehemently protesting against being provided with more than a single fiancée. When it was pointed out to him that according to immemorial precedent there should be not only one but several fei or secondary consorts, he replied that civilized monarchs in the West did not practice polygamy and he saw no reason why the Manchu court should countenance the practice.”

The Kangxi Emperor Made The Official Number Of Imperial Wifes 14 with the empress as the most important one -Source: Qingshigao

However, the custom of multiple wifes was a matter of prestige and tradition for the Qing court and after Puyi had actually abdicated from power even though he was still residing in the palace, prestige and tradition were all the court had left. Finally after much persuasion by officials and consorts, the emperor agreed to take one secondary wife. Notably seven years later this wife, Wen Xiu, would become the first ever court woman to be granted a divorce from an emperor.

New winds were indeed blowing in 1920s China, and at just about the same time as Puyi’s wedding plans were being made, Sydney Gamble published his famous social survey on Beijing. Here he reports that in the middle of the enormous social transformations that Beijing was undergoing, taking plural wives was a subject of much debate. Whilst on the one hand it was often heavily criticized, on the other it had actually become even more popular than ever before. The general upheaval of society norms made many people reach beyond their social status. With the collapse of the last dynasty, customs changed because the framework was gone. In a city such as Beijing, which in 1919 had a population that was 63 percent male, it is not so strange that taking more than one wife was seen as prestigious.

According to Gamble the practice had even spread to the lower classes. A friend of his was shocked to find out that his cook had three wives to feed on a fairly modest salary. This would have been unthinkable under the Qing, when people would have been careful not to do anything extravagant that did not correspond to their social status.

Gamble also explains how government officials too would often take many wives, and in a more gossipy part of the survey he describes how one such official was known to take a new wife every month, boasting about them as if they were racehorses.

Under the Qing, the emperor would ideally take fourteen wives. The empress would be the most important one, but each of the 14 had a title and officially recognized status that would entitle them to yearly endowments from the court, and even more importantly ensure that they would be taken care of for the rest of their lives. However, in private families, the secondary wives had an almost unprotected standing under the law. Secondary wives had no claim on inheritance, making them very vulnerable in the case of their husband’s death.

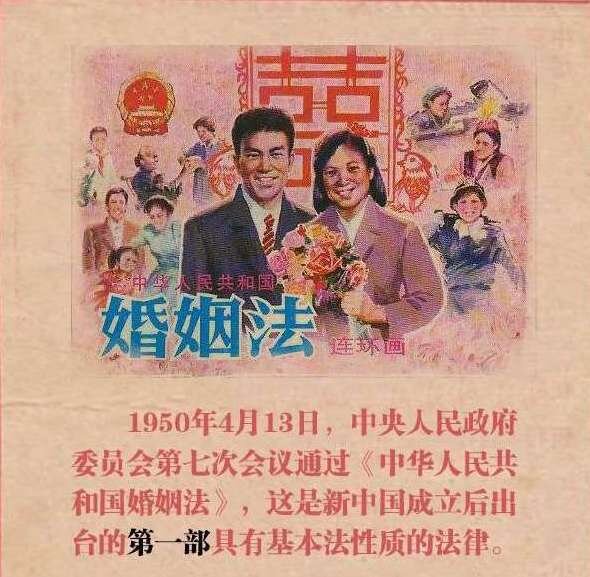

In the time following the abdication of the last emperor, many intellectuals in China were looking for a new modern identity. Confusing, passionate, and often heated discussions followed, and feudal customs were a main target of these debates. However, despite widespread criticism of the practice of multiple wives all through the Republican period, it took a revolution to finally abolish concubinage. When the communists took over one of the first things they did was to end all discussion and implement a new marriage law. A new order had been established with the new one party rule and having only one wife in every household became a reality almost overnight.

Interestingly, concubinage continued in Hong Kong even though the island was one of the first places to experience a strong movement against it after the territory came under British rule. The first suggestions to abolish the practice in Hong Kong dated back to as early as 1843, but it would take 128 years until the leftover Qing dynasty law was finally abolished in British controlled Hong Kong in 1971.