Beijing’s First Public Space and the Search for A Modern Chinese Identity

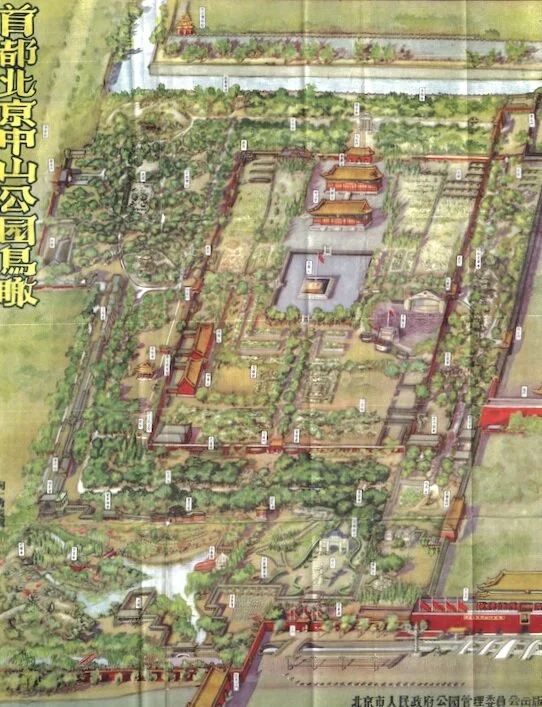

Bird's eye view of Zhongshan Park 1951

Next to the Tiananmen there is a red gate. It leads into a garden called the Zhongshan Park.

This small enclosure was the first ever public park in all of Beijing. At first the garden was called the Central Park, revealing that it was seen as the center of the new modern Beijing promised by the young Chinese Republic. Only after the death of Sun Zhong Shan, the president that led China’s transformation from dynasty to Republic, was it renamed the Zhongshan Park.

Today it is difficult to fully appreciate how groundbreaking this space was. We have grown accustomed to park life as a fundamental part of 21st century Beijing. However, when it opened in 1914, the park was truly revolutionary, a cultural and political melting pot, the likes of which the capital had never seen before. Suddenly, women who had previously been confined to the back of courtyard households were walking freely around and mixing with men. Modern-minded visitors could tiptoe along narrow maze-like lanes filled with all kinds of flowers and greenery. Enjoying their leisurely stroll, visitors to the park would pass a number of monuments. These were meant to act as a set of mental steppingstones, leading the visitor towards a whole new idea of China.

We have just collected a map of the park from 1951. Although when the map was made the Zhongshan Park was just about to lose its political significance after the Communist takeover, we can still use it to take an imaginary stroll inside a space where new thoughts and ideas once budded alongside the flowerbeds, catching glimpses of a very different China that would soon disappear.

A Dead German and the Apology that Disappeared

Entering the Zhongshan Park from the south, even today the first thing you see is the “Von Ketteler Memorial”. This massive stone archway was originally placed at Dongdan, and was erected to commemorate Clemens Von Ketteler a German minister to China who was shot dead by the Chinese Imperial army in 1900. It was Von Ketteler’s untimely death that caused the Boxer Uprising to spiral completely out of control. To make a very long story short, the Imperial government had sided with the popular Boxer movement in their attempt to rid China of foreigners and everything associated with them. It ended in war, and China lost badly. In the aftermath, Germany demanded an apology from the Chinese emperor for the killing of their highest representative. This came in the form of the archway, which was topped with a mournful statement written by the emperor Guanxu himself. The Boxer Rebellion was not only a conflict between China and the West, it was also a conflict of old versus new, or tradition against modernity. When the uprising ended with a year long foreign occupation of Beijing, a door had been opened into the capital. Universities, railways, paved roads etc. would now change the capital forever. The Zhongshan park itself was very much a part of this seemingly endless westernification to which Beijing was subjected. Many Chinese agreed with the changes, but the Boxer Rebellion and the force which with it was quashed remained controversial. When Germany lost the First World War, the archway was moved to its present location in Zhongshan park, where it was renamed the “Preserve Peace Archway.” On the way, the emperor’s apology that had been reluctantly given in the first place was taken down. The archway was now no longer protecting the memory of Von Ketteler, but commemorating atrocities committed by foreign powers against China.

Von Ketteler Monument 1910-19

Remembering atrocities committed against China was a common theme in the new modern park culture. Next to the Ketteler monument was a stone fountain that had originally stood at Yuanmingyuan or the Old Summer Palace before it was destroyed by the British army as an act of retaliation during the Second Opium War. Even today, the Yuanmingyuan remains maybe the strongest symbol of Western aggression against China. Ironically, large parts of the Old Summer Palace had been designed in a distinctively Western style, so when the British forces destroyed the palace in the mid 19th century some of the first European architecture ever built in Beijing became a Chinese national symbol.

The Old Sages Carrying the Roof of the Republic

Zhuqiqians Pavillion

This delicate balancing act between western and Chinese culture was a main theme that ran throughout Republican China. How could post-imperial China embrace something so radically different, and still be true to itself? Close to the Zhongshan park moat stands a pavilion. It was constructed by Zhu Qiqian, Beijing’s first Republican city planner, in an attempt to bridge Western and Chinese schools of thought. Zhu Qiqian was also the main man behind the Zhongshan park itself. The pavilion looks almost Greek in design, but the pillars originally bore quotations from the greatest Chinese philosophers like Mencius and Confucius. The idea was to show that the new emerging Republic, however modern, stood on the shoulders of the ancient Chinese thinkers. However, after the Communist takeover, the idea of creating a bridge between old and new lost out to a more revolutionary approach of simply annihilating the past in order to create a whole new society. As a result, during the Cultural Revolution the Red Guards destroyed the quotes from the old thinkers so that today only the barren pillars can be seen.

Lin Huiyin’s Suicidal Anger

The Alter & Zhongshan Hall

Not everybody in Communist China agreed with destroying the past. When the city government discussed the new city plan for Beijing, strong voices spoke up for preserving the layout of the old city. It was a clash between all kinds of leftover Republican intellectuals, and representatives of the new prevailing one party structure. Many of the most important meetings that debated this topic actually took place inside the Zhongshan Hall of the Zhongshan park. Renowned author Lin Huiyin stated at one of these meetings in 1952 that if the decision was made to tear down the left and right Changan gates just next to the Tiananmen, she would hang herself from one of them because of the irreparable damage it would do to the city. Lin’s suicidal anger did not seem to make a difference, and the moment the meeting was over workers that had been standing ready next to the gates tore them down, and the broad Changan Boulevard we know today was created. As a footnote it should be mentioned that whilst the voices of resistance were in vain, Lin Huiyin did not ultimately kill herself.

If a Tree Could Talk

Even though the Zhongshan Park was not opened till 1914, the compound itself actually has a much longer history. The garden was at first an altar ground constructed as an annex to the Forbidden City, and the emperor would come here and pray for a good harvest. By 1951, however, the emperor was long gone and right in the middle of the main altar a flagpole with the flag of Communist China was raised, leaving no doubt of who was in charge in new China.

The Zhongshan Park of today is only one of many public spaces in Beijing. At first glance, it is difficult to see the historical significance of this little charming space. The memory of the park’s high society heyday is preserved only in the yellow paged pictorials and maps of the Republic. But inside the park there are still a couple of inhabitants that have seen it all. The cypress trees found in the park are immensely old, some of them estimated to have stood for around 1000 years. It is fascinating to consider that these distinguished old organisms were present when high society ladies, university students, warlords and prostitutes mingled in their shadows. If only a tree could talk.