The Orthodox Monk who Brought China to Russia

Father Hyacinth Bichurin led the Russian Orthodox Mission to Beijing from 1807 to 1821. During his time in China he learned fluent Manchu, Mongolian and Chinese and made some of the most accurate Qing dynasty maps of Beijing. After returning to Russia, he founded the country’s first Chinese studies department in 1837.

Father Hyacinth Bichurin (1777 - 1853)

Father Hyacinth was a monk, but he was not just a monk – he was a champagne drinking, womanizing, cigar smoking kind of monk, and in the eyes of the Russian Church that was not considered acceptable behaviour, therefore he was recalled from China in disgrace in 1826. The accusations against Bichurin were in truth difficult to ignore. Two students had died of drink whilst working for the mission; church land had been sold off for profit; and Bichurin had all the way through his time in China arguably held a complete lack of devotion to God. Upon his arrival back in St Petersburg he was sentenced to house arrest in the Valaam monastery as punishment for his sins.

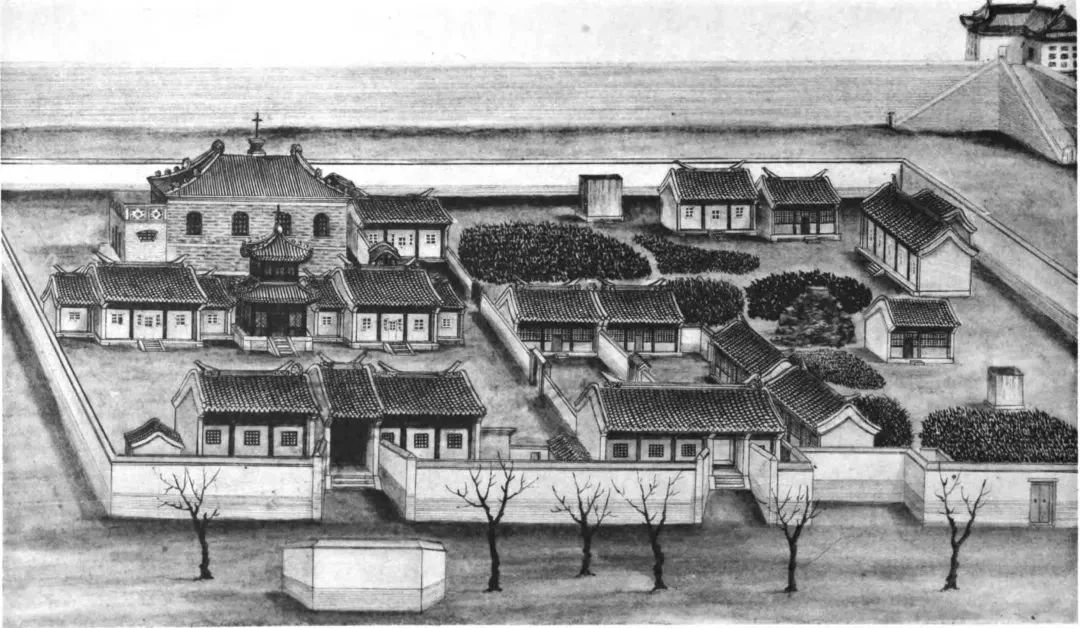

The Russian embassy to China of today is located where the Russian Orthodox mission established itself in 1713

However despite his very public disgrace, the monk maintained friends in influential circles within the Russian government, who appreciated the importance of the knowledge Bichurin he brought home about China. This knowledge was not only in Father Hyacinth’s head - he allegedly brought around 8000 kilos of Chinese manuscripts back to Russia with him. From his prison cell, he started to create an impressive body of work based on the information he had collected. This work was deemed so important to Russian imperial policy that when Bichurin tried to eventually retire, the Czar would not allow it.

44 Cossacks agreed to become elite soldiers of the the Qing dynasty, but brought their own Christian religion with them, allegedly forcing a priest to follow them to the Chinese capital

The reason for the curious tolerance of Bichurin’s misdemeanors within Russia can be found in the country’s history of diplomatic relations with China. Russian representation in the country started as early as 1650. In the aftermath of the 1685 Siege of Albazin on the Sino-Russian border, the emperor Kangxi gave the defeated Russian soldiers a choice - they could either return home or enroll in the Chinese army. 44 Cossacks accepted his offer, and allegedly forced a priest to remain alongside them. When the group arrived in Beijing, they were granted a plot of land – this land remains the location of the Russian embassy today. The soldiers were allowed to take Chinese wives, and even though they had built their own house of God, over time their descendants became increasingly absorbed into Chinese society. This prompted the Russian orthodox church to send missions to China to reignite the faith in the Russian enclave.

Father Hyacinth Bichurin created this map of Beijing in 1829 based on knowledge gathered during his 14-year stay (1802-1816) in the Chinese capital.

The Russian missionaries were very different from their Jesuit counterparts, because they did not actually aggressively seek to convert Chinese people to Christianity. The mission was focused on the spiritual salvation of the Russians within China, who the Russian government saw as important for maintaining foreign representation in the country at a time when few other foreign powers had this. However, prior to the appointment of Bichurin, the mission had not been of much diplomatic use. The Russian clergy looked down upon the Chinese, and had very little interaction with the locals. Things changed with Bichurin’s arrival. He walked the hutongs of the capital and befriended a host of people even deep inside the Chinese ministries. Bichurin was thus able to send useful information back to Russia – he all but forgot about doing god’s work and instead completely devoted himself to China studies.

Father Hyacinth Bichurin is recognized as the father of Russian Sinology

His unique knowledge of the inner workings of Chinese society made Bichurin a minor celebrity. He befriended some of the most important people in Russia, among them the author Pushkin. Such was Bichurin’s devotion to China that at times he was accused of relying too heavily on Chinese sources in his work, however when he died even his staunchest critics had to admit that nobody meant as much to Russian orientalism as this cigar smoking monk.